Byeong Chul Kim, President of Misung Commercial Co., Ltd.

Chapter 7. Indonesia: The Beginning of a New Challenge

BNB Magazine resumes the memoirs of President Byeong Chul Kim of Misung Commercial Co., Ltd. in this issue, following the earlier six-chapter serialization. Based on President Kim’s vivid recollections, the series chronicles the history of the wig industry during that era, spanning both Africa and Indonesia.

President Byeong Chul Kim at the Indonesian Branch Office

Previous Story

[In 1967, President Byeong Chul Kim joined Samchully Briquette Co., Ltd. Five years later, in 1972, when the Samchully Group acquired Misung Commercial Co., Ltd., he was unexpectedly transferred to the wig business. With no prior knowledge, he learned step by step through countless trials and errors. In 1983, he was dispatched to Senegal for Misung Commercial’s African expansion. Starting from scratch, he built a factory on barren land and successfully launched the ‘NINA’ hair brand. What was meant to be a one-year assignment in Africa stretched into a full decade of pioneering work…] –

A New Starting Point

In late 1992, after ten years under Senegal’s scorching sun, I received an urgent call from headquarters. I had begun to wonder, “Isn’t it time I returned to Korea?”—but the company had other plans.

Back in Seoul, major changes were underway: a new CEO, large-scale restructuring at Misung Commercial, and then the surprise. Along with the title Vice President in Charge of Overseas Operations came a bombshell assignment:

“Vice President Kim, you are being dispatched as local president in Indonesia. Please establish the factory there.”

Departure was set for January 1, 1993. The order was sudden, and with Misung’s Senegal subsidiary preparing for its 10th-anniversary celebration, I had to attend both the anniversary and my farewell within two months. And so, another chapter of life in an unfamiliar land began.

Fateful Encounter

At that time, traveling from Africa to Indonesia meant a complicated route: Dakar → New York → Seoul → Jakarta. Yet even on this long journey, a fateful encounter occurred. On the flight from New York to Seoul, I met a chairman of a U.S. hair business. News had already spread in the industry that Misung had a new president and that Byeong Chul Kim from Africa was taking charge of overseas operations in Indonesia. The chairman consistently addressed me as “President Kim.” During our long conversation, he gave me advice that set my first objectives in Indonesia:

“President Kim, the Indonesian factory hasn’t received positive feedback on quality. When you go, please focus on improving wig quality.”

That single conversation defined the initial direction of my work in Indonesia.

Taking the First Step

Upon arriving in Indonesia, I focused first on understanding the local situation. I couldn’t simply overhaul a factory that had already been managed by my predecessors for a year—observation had to come before action. What I considered most important was communication with the local managers, particularly the Korean female forewomen dispatched from the home factory to oversee operations. To build closer ties, I made an unusual request: a room in the women’s dormitory.

For a male superior, it was hardly comfortable—for either side. We had to be discreet in using shared facilities, and every interaction required caution. Yet this unique arrangement helped me earn the forewomen’s trust and gain a realistic understanding of relationships on the ground.

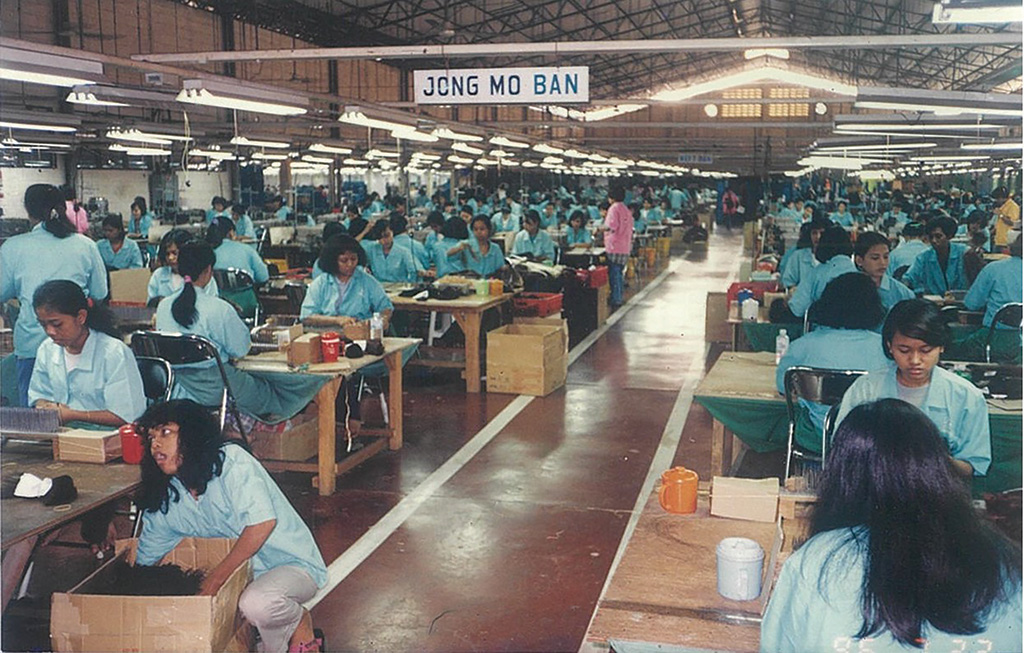

View of Jakarta Factory No. 1, Indonesia

The Battle Against the Language Barrier

One of the greatest challenges I faced in Indonesia was the language barrier. Before going to Africa, I had at least managed to learn some basic French, but my transfer to Indonesia was so sudden that I had no time to prepare. On one occasion, after finishing an off-site meeting, I stepped outside the building, only to discover my driver and car were gone. The interpreter had told the driver “Pergi 하지 마!”—a mix of Indonesian and Korean meant to say “Don’t go.” But the driver understood only “Pergi” (go) and promptly drove off.

Similar misunderstandings were common at the factory: instructions meant for the right side were carried out on the left, or measurements were interpreted incorrectly.

My solution was to develop extremely precise specifications. Guide drawings alone weren’t enough, so I added detailed notes in Indonesian and listed every step prone to error. Over time, the specifications became so complex that people joked, “Misung’s specs are like building an airplane.” Yet I believe it was precisely this level of detail that gave Misung products their exceptional quality.

Starting with Small Changes, Shifting Our Mindset

As I struggled to adapt and find ways to unite the staff, one detail struck me: Indonesian employees would never pick up a trash on the floor. Their thinking was, “That’s the cleaner’s job, not mine.” Once, when I picked up one, an employee kicked more trash toward me and said, “Pick this up too.” It wasn’t laziness but a deeply fixed mindset about divided roles. Changing this way of thinking became my top priority.

We began by holding a weekly factory-wide assembly every Monday, starting each session with Indonesia’s national anthem, Indonesia Raya.

I emphasized, “This is not a Korean company expanding overseas. This is an Indonesian company.”

Instilling pride was crucial. At first, employees sang hesitantly, but over time their voices grew stronger. I, too, learned to sing Indonesia Raya as confidently as my own national anthem, knowing the staff were watching closely to see if their president truly sang with them.

Factory-Wide Assembly at Jakarta Factory

If You Don’t Know, Ask

When it came to reducing defects and improving quality, nothing was more important than employees fully understanding their tasks.

I always emphasized: “If you don’t know something, ask. The more you ask, the more you learn.”

But encouragement alone wasn’t enough—we needed a system that made questions and answers quick and clear. So, we introduced color-coded uniforms by role: foremen in red, inspectors in blue, and general workers in white.

Each workstation also had a small flag; raising it signaled the foreman for immediate support.

With these measures, employees grew more confident, and pride followed: “Our company is a great company, our workshop is the best workshop.” Over time, Misung earned a reputation for developing skilled workers, and being from the “Misung Wig Factory” became a credential welcomed by other factories.

Training Session for Foremen at Jakarta Factory

Laying the Foundation, One Step at a Time

While training employees, I also focused on improving the factory floor. Each time I walked in, I saw countless issues waiting to be fixed. I replaced scissors that took several cuts to trim a single thread, swapped out sewing machines with broken needles and frayed threads, adjusted chairs to fit workers’ heights, and installed brighter lighting.

I believed that addressing these problems one by one was the true foundation of quality improvement, and I worked with unwavering determination. As these changes took root, the Indonesian Misung factory slowly began to transform. But this was only the beginning.

< Continued in the next issue>